Context: Indians are shifting from subsistence needs to aspirational and service-oriented spending.

- The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoS&PI) captures spending pattern of Indian households across various consumption categories.

- Conducted every five years, the HCES provides granular estimates of Monthly Per Capita Expenditure (MPCE) for both rural and urban populations, covering a wide range of goods and services.

- The survey rounds for 2022-23 and 2023-24 represent the first comprehensive update to MPCE data in over a decade, offering valuable insights into India’s shifting consumption landscape. These findings are central to revising poverty estimates, informing social sector policy, and understanding the lived realities of India’s expanding middle-income population.

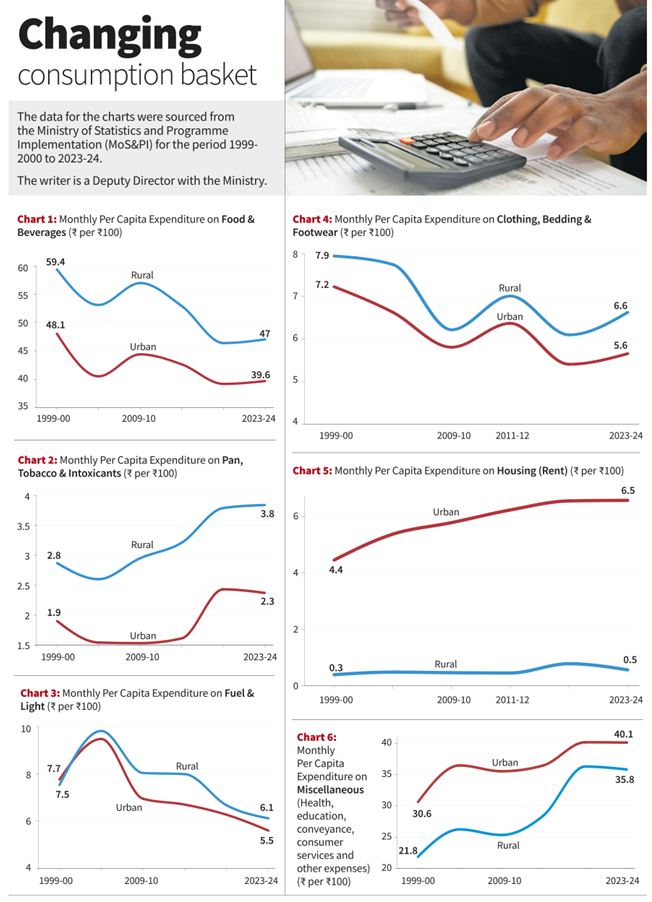

- This article examines long-term MPCE trends from 1999-2000 to 2023-24, with a focus on six key expenditure categories. In this analysis, MPCE is expressed as the proportional expenditure on an item for every ₹100 of total spending.

- Decline in MPCE share on food and beverages for both urban (from ₹48 to ₹39 per ₹100) and rural areas (from ₹59 to ₹47 per ₹100) confirms Engel’s Law, which states that as real income rises, the proportion of income spent on food declines, even if absolute expenditure increases. (Chart 1)

- Further, a fall in expenditure on cereals, alongside higher spending on fruits, eggs, fish, and processed foods, signals a shift from staple-heavy diets to more varied, protein-rich diets — albeit unequally.

- Despite marginal increases, particularly in rural areas, spending on pan, tobacco, and other intoxicants remains a low share of MPCE, accounting for under ₹3.8 per ₹100 of spending. From a public health perspective, the trend calls for targeted awareness programs in rural belts. (Chart 2)

- The reduction in per capita fuel spending reflects policy successes, such as Saubhagya (rural electrification) and PM Ujjwala Yojana (LPG access). Lower urban spending may also reflect the use of energy-efficient appliances and access to reliable power supply. Modern fuels, in place of biomass or kerosene, improve quality of life and are an example of expenditure substitution. (Chart 3)

- The decline in spending on clothing, bedding and footwear is moderate and consistent with the transition from need-based consumption to periodic discretionary spending. Rising competition, fast fashion, and lower textile prices may also have contributed. Rural India’s slightly higher or similar spending may indicate seasonal dependence and growing aspirations. (Chart 4)

- The urban housing rent share rose significantly (₹4.46 to ₹6.58 per ₹100), aligning with urbanisation, rental stress, and migration to metropolitan hubs. Rural rent remains minimal due to widespread self-owned housing, informal tenure, or rent-free arrangements. (Chart 5)

- The miscellaneous category includes aspirational expenses such as health, education, conveyance, consumer services, and other similar costs. Its rising share, particularly in rural MPCE (from ₹21.87 to ₹35.82 per ₹100), reflects a broadening of the consumption basket. This trend aligns with inclusive growth, deeper digital penetration, and echoes improved reach and quality of both public and market-based services. (Chart 6)

- Taken together, these trends reflect that society is undergoing an economic transition, with consumption patterns gradually shifting away from subsistence needs toward more aspirational and service-oriented spending.

Source: The Hindu